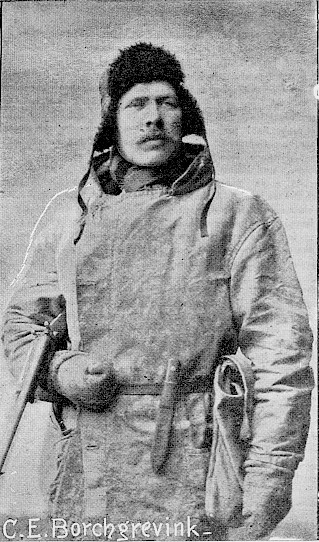

Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink ('Borchy', 1864–1934)

Borchgrevink and Kristensen each wrongly claimed to have been the first to walk on the Antarctic continent on the 24th January 1895: earlier landings of sealing voyages were probably initiated by American sealer Captain John Davis in Cecilia, landing at Hughes Bay in 1821. Borchgrevink was a deck hand on the hunt for Right whale in the ship Antarctic, but also completed scientific work, collecting rocks and lichens. Therefore, Borchgrevink can be credited with being the first aiming to advance science on the Antarctic continent. Despite being considered an amateur scientist in England, his Antarctic report to the 6th International Geographical Congress in London in 1895, his lectures, and journal and newspaper articles, renewed interest in Antarctic exploration and science.

Education and work

While Norwegian born, educated at Gjertsen College and the Royal Forestry School, Tharandt, Saxony, he arrived in Australia in 1888. He worked in Queensland and New South Wales, and taught at the Cooerwull Academy from 1892–1894, before his first Antarctic voyage. This experience ignited his desire to return and be the first to winter in Antarctica.

As leader of the 1898–1900 voyage

Unable to obtain funding from government sources in Australia or England, Borchgrevink accepted Publisher Sir George Newnes’ finances for Borchgrevink’s 10 man team and 75 sledge dogs to sail in the Southern Cross to be based at Cape Adare during the Antarctic winter. The multicultural team, under the British flag comprised of Norwegian, Finnish, British and Australian men, with a focus on meteorology, magnetism, and zoology. Tasmanian Scientist Bernacchi made a significant contribution on a scientific and interpersonal level.

Expedition achievements

Borchgrevink’s expedition established themselves as world authorities on Antarctic research and survival. Their hut design was well considered, having insulation and a double glazed window. The expedition was successful in locating the position of the South Magnetic Pole. During a sledging trek, they reached 78° 50' S, the highest southern latitude reached at that time. They were the first to use a canvas kayak in Antarctica. Among many samples, they collected the first Antarctic insects. Antarctic seaweed obtained on the expedition was provided to the Natural History Museum in London. They recorded meteorological and magnetic data throughout the year.

Borchgrevink’s contribution to science was recognised in many countries, including Norway, Denmark, Austria, and Scotland but it was not until 1930 that Borchgrevink was awarded the Patron’s Medal by England’s Royal Geographical Society. Borchgrevink’s account of the expedition First on the Antarctic Continent was published in 1901, after which he studied volcanic eruptions in the West Indies.

Family

It is likely that he met and married Englishwoman Constance Prior Standen, while securing finances for his 1898 voyage. Upon his return from Antarctica, they lived in Oslo, having 4 children, 2 sons and 2 daughters. Borchgrevink’s love of nature was passed on to his son Ridley, who became a painter and book illustrator to the Marine Algal collection.

Personal attributes

Although described as dedicated, passionate and enthusiastic, he could also be moody, unforgiving, and guarded. Overall, his desire to extend Antarctic science seems to be for personal adulation. The death of Hanson, Zoologist, was glossed over in Borchgrevink’s account, and yet explained with detail, compassion and understanding by Bernacchi. While minimising Hanson’s death may have been Borchgrevink’s way of coping in his leadership role, it is more likely that Borchgrevink did not want Hanson’s death to detract from his own glory.

Despite his faults, Borchgrevink was courageous and determined to succeed. At Cape Adare, they had no means of communication (this was before radio), and no knowledge of the continents creatures. They took weapons in case they encountered predators, such as polar bears. Being responsible for the lives of 10 men in an unknown land, while having to prove his skills to the scientific community must have been a daunting challenge and one that he carried to its successful completion.

Written by K Quinn